Medically reviewed by: Univ. Prof. Dr. Christian Gäbler

Last updated: 17.02.2026 | Reading time: approx. 9 min.

A wrong step while playing football, a fall while skiing or simply twisting your ankle in everyday life: a torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL rupture) is one of the most common knee injuries. However, the diagnosis does not automatically mean major replacement surgery.

At Sportambulatorium Wien, we employ a differentiated strategy: wherever possible, we try to preserve the patient's own cruciate ligament (refixation). If replacement is necessary, we use state-of-the-art, minimally invasive techniques (all-inside). Our goal is not only to achieve a stable knee, but also to enable you to return to sport quickly and safely.

Symptoms & signs: How a cruciate ligament rupture presents itself

Many patients are unsure: ‘Have I torn my cruciate ligament or is it just a strain?’ In fact, pain perception is very individual. Some patients experience severe pain, while others have virtually no symptoms. However, there are some typical symptoms you should look out for:

- The noticeable ‘popping’: Many patients report a painful popping, cracking or crunching sound at the moment of the accident.

- Instability (‘giving way’): Probably the most important key symptom. You feel as though your knee is ‘slipping away’ or giving way.

- Swelling: In most cases, the knee swells severely within a few hours.

- Restricted movement: The knee often cannot be fully extended or bent.

Expert tip: The deceptive course of pain

A cruciate ligament rupture may cause little or no pain at times. This surprises many patients. The explanation: the pain-conducting nerves are not primarily located in the cruciate ligament itself, but in the surrounding joint mucosa. If this remains largely intact when the ligament ruptures, the initial pain often subsides quickly.

⚠️ A dangerous fallacy: Please do not believe that ‘if it no longer hurts, nothing has happened.’ A torn cruciate ligament does not usually heal on its own. Without treatment, the knee remains unstable, which drastically increases the risk of further damage.

What you need to look out for: It is not how it feels now that is decisive, but the moment of the accident. Almost all patients report sudden, severe pain and the feeling that ‘something snapped or broke’ in their knee. Have you experienced this ‘popping’ sensation? If so, have your knee examined by an orthopaedic specialist – even if you are currently almost pain-free.

Can you still walk with a cruciate ligament rupture?

Yes, this is often possible. Since the thigh muscles can stabilise the knee, many patients are able to limp or even walk normally shortly after the accident. However, any further ‘buckling’ risks serious damage to the meniscus and cartilage. Therefore, put as little strain on the leg as possible until you have been examined by a doctor (use crutches, immobilise the leg).

Diagnosis (drawer test & MRI)

A precise diagnosis at Sportambulatorium Wien always consists of two steps: a clinical examination by our specialists and confirmation through imaging.

1. The clinical examination (drawer test & Lachman test)

Before taking any images, we check the mechanical stability of your knee joint. Experienced sports traumatologists use very specific techniques to do this:

- Lachman test: The doctor pulls the lower leg forward with the knee slightly bent. If it can be moved without resistance, the anterior cruciate ligament is probably torn.

Anterior drawer test: Similar to the Lachman test, this test checks how far the shin bone can be pulled forward relative to the thigh (‘drawer’).

2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – Why X-rays are not enough

A normal X-ray only shows bones, but not ligaments. To confirm a cruciate ligament rupture with certainty, an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan is essential.

Our service: We will be happy to arrange an appointment for you at a specialist X-ray institute at short notice. The images taken there will then provide us with the information we need to plan your treatment:

- Is the ligament completely torn?

- Where is it torn (important for the decision: repair or replacement)?

- Are there any accompanying injuries to the menisci, cartilage and/or collateral ligaments?

Do you have an unstable knee?

Play it safe. Book your appointment now for a clinical examination and MRI consultation.

Just give us a call!

Treatment decision: Does a cruciate ligament rupture always require surgery?

This is probably the most common question our patients ask. The clear answer from Univ. Prof. Dr. Gäbler is: No, not always – but often.

We do not treat MRI images, but people with individual goals. The decision depends primarily on stability and your activity level.

Conservative treatment (without surgery)

A tear can be treated conservatively (through physiotherapy and muscle building) if:

- It is a partial tear or a strain.

- You do not participate in ‘stop-and-go’ sports (football, tennis, skiing).

- You do not feel unstable in everyday life.

- You are prepared to engage in muscle training on a long-term basis.

Surgical treatment

We recommend surgery if you are physically active or if your knee is unstable in everyday life. Anyone who plays sports such as football, volleyball or skiing without a stable cruciate ligament risks serious long-term damage.

The risk of waiting: consequential damage to the meniscus and cartilage

Why do we operate on athletes?

The main problem is instability. Dr Gäbler warns: "If the knee constantly tilts or gives way slightly, the menisci – the joint's shock absorbers – are subjected to enormous continuous stress. This can cause considerable damage in the long term. Surgery therefore also protects the rest of the knee.

Vergleich: Konservativ vs. Operativ

| Factor | Conservative treatment | Surgical treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Target group | Less active patients, elderly people | Athletes, active people |

| The advantage | No surgical risks, immediate rehabilitation | Full stability & athletic ability |

| The disadvantage | Risk of meniscus damage remains high | Anaesthesia, surgical risk, extended break |

| Return to sport | Only to a limited extent (no pivot sports) | Completely possible (after approx. 9-12 months) |

The ideal time for surgery: why the ‘7-10 day window’ is crucial

There is often a myth that a cruciate ligament must be operated on within 24 hours. This is incorrect. Rushed surgery is not necessary and does not correlate with current research. However, there is an optimal medical time window, which we use at the sports clinic.

The Golden Window: Days 1 to 10

The current study situation shows that surgery is ideally possible within the first 7–10 days after injury.

- Advantage: The knee is not yet inflamed.

- Additional benefit: Frequent accompanying injuries to the meniscus can be treated (sutured) immediately, which drastically improves the chances of recovery.

Don't miss the ‘golden window’!

Check now whether immediate treatment (days 1–10) is possible for you.

Just give us a call!

The ‘prohibition phase’: Day 10 to week 6

After about 7–10 days, a natural inflammatory reaction (swelling, warmth) begins in the knee. During this phase, surgery should not be performed under any circumstances!

- Strategy: If the knee is already inflamed, we wait until it is no longer irritated (usually after 6–8 weeks) before operating.

- Strategie: Ist das Knie schon entzündet, warten wir ab, bis es reizfrei ist (meist nach 6 – 8 Wochen), bevor wir operieren.

Our advice: Have the diagnosis made by MRI as soon as possible. This is the only way we can take advantage of the ideal window of opportunity for early treatment.

The surgical methods in detail: preservation before replacement

At Sportambulatorium Wien, we adhere to one ironclad principle: We save the patient's own ligament whenever possible. Only when the cruciate ligament is irreparably damaged do we resort to replacement (tendon replacement surgery). This distinction sets us apart from many clinics that routinely perform replacement surgery as a matter of course.

1. Cruciate ligament preservation (refixation): Saving your own ligament

In approximately 10–20% of cases (often in children, adolescents or recent injuries), the cruciate ligament is not torn in the middle, but torn directly from the bone. This is a stroke of luck in an unfortunate situation.

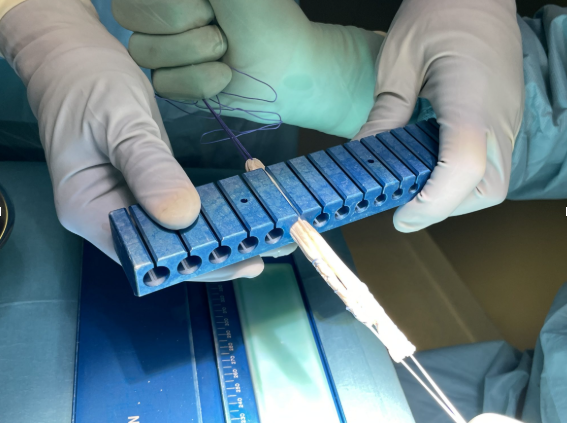

- The method: We can reattach the ligament to its original position using a minimally invasive technique. We use special dowel pins for this purpose.

- The bio-booster (‘healing response’): To ensure that the ligament grows back securely, we also drill tiny holes in the bone. This causes stem cells to emerge from the bone marrow, which greatly accelerates biological healing.

- The advantage: you retain your own ligament and thus also the important nerve fibres (proprioceptors) that are crucial for your sense of balance.

2. Cruciate ligament replacement (ACL reconstruction): The ‘all-inside’ technique

If the ligament is frayed in the middle, it must be replaced. Here, we rely on the latest evolution in cruciate ligament surgery: the all-inside technique.

What is the difference compared to conventional surgery?

- Classic: Complete drill channels are drilled through the lower leg and thigh bones. This is traumatic for the bone and often causes pain.

- All-Inside (our method): We only drill so-called ‘blind holes’ (blind-ended tunnels) from the inside. The outer bone shell remains intact.

- Your advantage: Less bone pain, smaller scars, better cosmetic results and extremely stable anchoring with special ‘endobuttons’.

Which material? Choosing a replacement tendon

For cruciate ligament reconstruction, we need a tendon to replace the torn cruciate ligament. We discuss which tendon to use on an individual basis, depending on sporting requirements, stress profile and personal goals.

- Quadriceps tendon (gold standard): The quadriceps tendon is the strongest replacement tendon available and offers excellent stability. It is particularly used for patients who are motivated by sport. Removal is reliable, the results are very good, and the tendon is ideal for high loads and demanding sports.

- Semitendinosus tendon / hamstring (former gold standard): The tendon is harvested through a small incision in the skin. The results are generally good, but there is a slightly higher complication rate, particularly due to possible injury to sensitive skin nerves. In addition, there may be a measurable weakening of flexion strength and internal rotation, which may be particularly relevant for performance-oriented athletes.

- Patellar tendon / BTB (now used only very cautiously): The patellar tendon was frequently used in the past, but now plays only a minor role. The reasons for this are an increased risk of pain when kneeling (anterior knee pain), discomfort behind the kneecap and an overall less favourable load situation in everyday life and sport.

- Allograft (Spendersehne):

- Für wen? Ideal für Revisions-OPs (wenn schon einmal operiert wurde) oder Top-Athleten, die keine eigene Sehne „opfern“ wollen.

- Ist das sicher? Ja. Wir nutzen ausschließlich BioCleanse®-behandelte Sehnen, die steril sind, aber nicht bestrahlt wurden (daher volle Reißfestigkeit).

Professional sports example: Italian Olympic skiing champion Sofia Goggia successfully competes in the World Cup with a donor tendon.

Recovery time & rehabilitation: When can I start exercising again?

First, the good news: in over 90% of patients, modern cruciate ligament surgery restores full function, mobility and strength. However, the operation is only half the battle. Professor Gäbler emphasises: ‘50% of success depends on the surgeon, 50% on the patient and consistent rehabilitation.’

The ‘foreign body sensation’ (proprioception)

Many patients initially report: ‘It feels as if the knee doesn't belong to me.’ This is because the torn ligament also caused the loss of nerve cells (receptors) that report the position of the knee to the brain. Targeted coordination training (e.g. on the MFT board) helps these receptors to regenerate. This feeling usually disappears completely within 6 to 24 months.

Your timeline for returning

Every progression is individual, but as a rough guide for athletes, the following applies:

- Weeks 1–2: Physiotherapy begins on the first day. Walking with crutches (full weight-bearing is permitted), immobilisation using orthoses, elevation and lymphatic drainage.

- From week 2: Intensification of physical therapy and increasing walking without crutches.

- After 8 weeks: Start with ergometer training and swimming (front crawl) as well as increasing strength and coordination training.

- Months 3–4: Light running training (jogging) on flat ground is often possible again.

- Months 6–12 (return to sports): After approx. 6 months, return to running sports only. After 9–12 months, return to “stop-and-go” sports (soccer, skiing) – always dependent on good muscle development and a successful muscle test.

Special cases: cruciate ligament rupture in children and the elderly

At Sportambulatorium Wien, we don't treat everyone the same. A 12-year-old athlete needs a different strategy than a 70-year-old hiker.

Cruciate ligament rupture in children and adolescents

Injuries in children are often overlooked or downplayed. This is dangerous. The research is clear: not operating on an unstable knee in children leads to massive consequential damage.

- The risk: A study (Orthop J Sports Med 2021) shows that with each year of waiting, the risk of a meniscus tear increases by 16–20%. Delaying surgery for more than 12 weeks also significantly increases the risk of irreparable damage.

- Our recommendation: In cases of instability, we operate as early as possible. In children in particular, the chances of preserving their own ligament (refixation) are very high, as the ligaments often tear away from the bone.

Are you concerned about your child's knee injury?

Cruciate ligament rupture in seniors (over 60)

It used to be said that “you don't operate on cruciate ligaments in old age.” We see things differently. People who only go for walks often only need physiotherapy (muscle building). But for active seniors who want to play tennis or ski, surgery is often the only way to maintain their quality of life. We decide on a case-by-case basis (often a donor tendon/allograft is ideal so that the patient's own tendon does not have to be removed).

Conclusion: Don't be afraid of the diagnosis

Nowadays, a torn cruciate ligament is no longer a reason to give up sports. Whether preservation (refixation) or replacement (all-inside): with the right diagnosis and ideal timing, we will get you back on your feet.

Do you have pain or an unstable knee? Don't wait until you develop meniscus damage.

Vereinbaren Sie jetzt Ihren Termine:

💬 Online via Kontaktformular

📞 Tel: 01 4021000

✉️ Mail: office@sportambulatorium.wien

You may also be interested in

Scientific sources & studies

The content of this page is based on the clinical experience of Univ. Prof. Dr. Gäbler and current international studies in sports traumatology:

- Risiko von Meniskusschäden bei Kindern (BMI & Alter): Perkins CA et al.: Rates of Concomitant Meniscal Tears in Pediatric Patients With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries Increase With Age and Body Mass Index. Erschienen in: Orthop J Sports Med. 2021

- Vergleich: Frühe vs. Späte OP bei Kindern: James EW et al.: Early Operative Versus Delayed Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment of Pediatric and Adolescent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Erschienen in: Am J Sports Med. 2021

- Vorteile der frühen Rekonstruktion: Kay J et al.: Earlier anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is associated with a decreased risk of medial meniscal and articular cartilage damage in children and adolescents. Erschienen in: Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018

- Arthrofibrose-Risiko: Studien des Karolinska Institut, Stockholm: No risk of arthrofibrosis after acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Erschienen in: Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018